The Five Senses of a Blue Whale

The Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is the largest animal known to have ever inhabited the Earth. Spanning up to 32 metres in length and weighing up to 200 tonnes, with a tongue comparative in weight to an elephant. The species inhabits every ocean of the world except for the Arctic and undergoes annual migrations from the nutrient rich polar waters of the Antarctic. Towards the equator, with the arrival of Winter to mate and give birth.

Blue whales are currently listed as an endangered species due to as much as 99% of the population being decimated by the whaling industry in the 17th – 20th century. Although recovery has been particularly slow in the last few years. There has been evidence that the population is increasing with an estimate of 5,000 – 15,000 mature individuals dispersed world-wide. Blue whales’ senses include hearing, sight, and touch, similar to terrestrial animals. However like many other cetaceans they have a limited capacity to smell and taste.

Navigating the darkness of the ocean through sound

Blue whales can hear up to 1000 miles away in optimal oceanic conditions. Using their vocalisations which involve a series low frequency moans, pulses, and groans which are typically within the range of 14-40 Hz. To both communicate and sonar-navigate the depths of the ocean in the absence of light. In the ocean sound travels further and four times faster than in air. So therefore hearing is arguably the most important blue whale sense. They can also create the largest sounds made by any animal. Up to 188 decibels which is like the sound emitted from a rocket launch platform. Which can be heard throughout an ocean basin!

Blue whales’ ear structures are highly specialised for hearing underwater as they primarily rely on sound for communication. And most significantly sensory perception. Although they have no external ears, the bones housing the inner and middle ears in blue whales are separated from the skull. With sinuses around each ear, enabling them to isolate and determine the direction of a sound.

The songs and vocalisations of a blue whale can be related to behaviours including navigation, aggression, and courtship. Although blue whales are quite often solitary, their vocalisations can be used to distinguish between different geographical populations. As blue whales living in the same area vocalise for the same duration, in the same patterns and at the same frequencies.

Feeling for food

Touch has been a widely observed whale sense to play an important role in cetacean social relations. Most significantly between mother and calf. Touch is also particularly well developed near the blowholes and around the head in whales for the purpose of allowing the blowhole to open for breath. Once the ocean’s surface has been detected. Blue whales possess whisker like hairs on the ends of their rostrums and around their head, known as vibrissae. These are especially useful in low light conditions, enabling them to essentially ‘feel for their food’. Due to the follicles being connected to a large nerve bundle by dense connective tissue.

Eye can’t see you (that well)

Due to the way that light is scattered through the ocean, turbidity resulting in low visibility. The decrease of light with increasing depth, sight is a less effective sense of the blue whale. In association to their body size, blue whales have relatively small eyes with weak eyesight, compared to other animals. The lens of a marine mammal must be stronger than a terrestrial mammal to enable vision in the ocean. This is more like the lens of a fish to compensate for the lack of refraction to the cornea.

Baleen whales such as blue whales have eyes which are sensitive to mostly low-level light due to the increased presence of “rod cells”. With limited “cone cells” which are associated with bright light. Which assist in distinguishing between colours. As a blue whales’ eyes are constantly exposed to salt water. They possess oil secretion glands on their outer eyelids which clean and lubricate their eyes.

If blue whales could taste, would they still be interested in solely consuming krill?

Cetaceans do not have the same strong sense of taste or importance associated with taste as humans do. The sensation of taste has not been very well studied in baleen whales and it is debated whether they can even taste at all. Despite the visible taste buds on their large tongues. Blue whales feed almost exclusively on krill, and in Antarctica during the height of the feeding season. Large, adult individuals consume 3-4% of their own body weight, eating as much as 6 tonnes of krill a day.

Using the baleen plates which work like a sieve and hang from the roof of their mouth. Blue whales can strain ocean water whilst swimming towards school of krill, using their tongue to push water out of their mouth, retaining their catch inside. As blue whales swallow their prey whole. Taste may also be irrelevant to the species. As they do not engage in a chewing motion which is typically associated with the release of flavour.

Lack of smell

Similarly, to a blue whales limited ability to taste. Their sense of smell is also reduced in comparison to their more significant senses such as hearing. In water, molecules diffuse at a slower rate than in air, which contributes to smell beneath the ocean less effective. Especially for marine mammals such as the blue whales which can reach top speeds of 35 km/h. Baleen whales including the blue whale, do possess a small vomeronasal organ however. This allows them to detect pheromones and chemicals, like the human sensation of smell.

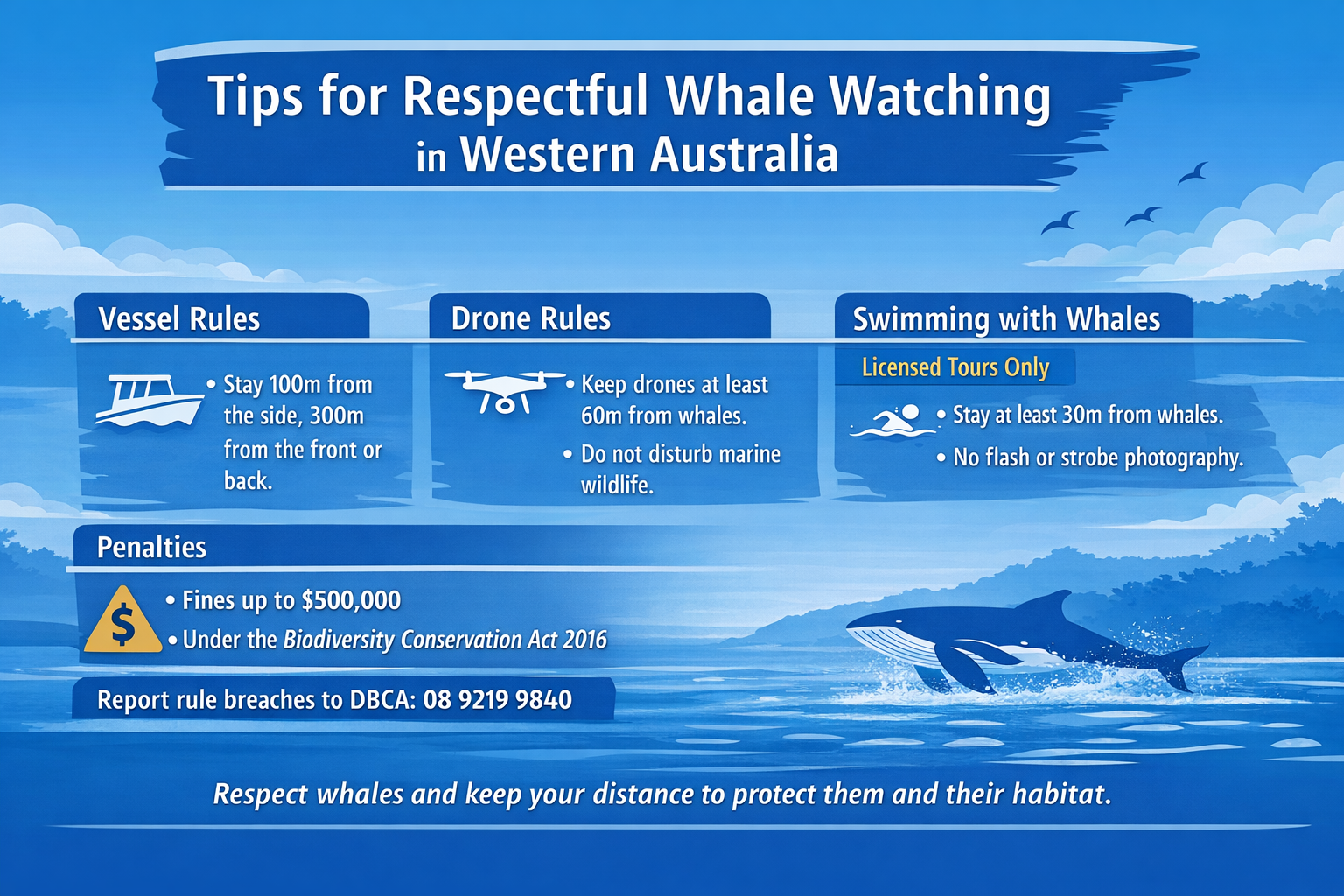

Blue whales are a mysterious species with so much research left to be conducted. Due to their elusive nature and the challenges that come with studying them in their ocean environment. Naturaliste Charters conduct Western Australian whale watching tours daily from December through to April at the Bremer Bay Canyon. This is currently the only documented location that killer whales have been recorded killing and eating blue whales in the world. Tours also depart daily from May to August in Augusta, and September to early December in Dunsborough. Which encompasses part of the coastline that blue whales annually migrate past on their journey from Antarctica. Each expedition is led by an expert marine biologist and an experienced team. Providing passengers with an extremely high chance of observing these giants of the ocean.