“The condition of being imprisoned or confined”

This is the definition of captivity and is the theme of this blog post. Below we delve into orcas in captivity, we will be touching on the history, issues, fate of these animals, how we can educate people, how many orcas are in captivity in 2021 and more.

Captive animals can shed light on biology and physiology that cannot be observed in wild populations. For example psychology, cognition and immunology. Captive studies have also heavily contributed to acoustics and physiology. However advances in technology have allowed scientists to conduct low impact sampling of wild populations and gather the same amount of data as the highly invasive techniques on orcas in captivity.

Please note this blog does contain graphic content and advises sensitive readers to continue with caution.

History of orcas in captivity

Throughout history there have been occasional reports of marine mammals, such as orcas, kept in captivity. However the debate about whether or not this is an ethical issue has only come about in recent times.

A new era of captivity began in the 1930’s with dolphins and belugas in a New York museum. From 1950 to 1970 the rise in aquariums and zoos displaying marine mammals increased rapidly. Synonymous to this, the technology and capabilities of humans to capture, transport and maintain enclosures grew. Scientists also took advantage of available specimens to conduct invasive and easy research.

Public opinion of orcas in captivity

Public opinion shifted in the 1980’s and nongovernment agencies forced the closure of some facilities as animal ethics were of concern. The more we watched orca behaviour in captivity, the more we began to understand how intelligent they are. This was both a discouraging and encouraging reason to keep them under close observation.

Australian and European captive mammals saw a decline due to societal pressures but other countries such as Asia, increased their efforts.

There are no international laws for captivity, unlike whale hunting. Certain countries such as Norway have their own national ban on keeping cetaceans like orcas in captivity, but this cannot carry over to other countries. Each individual government decides on how to administer and enforce such laws.

Issues with keeping an intelligent apex predator in captivity

There are many issues surrounding keeping an intelligent apex predator outside their natural environment. This is increased ten-fold for a large marine mammal.

Not only physical but psychological impacts occur on the animals and only for the gain of human interest and pleasure. The most disappointing issue surrounding captive animals is not providing any education or conservation efforts for the species. It may sound simple but not all “businesses” are managed on strong animal morals and ethics.

Below we will go into a few behaviours developed by orcas in captivity and their natural/wild equivalent.

Premature death

Only two captive orcas have reached the average equivalent of their wild counterparts. Although they receive world-class care and food delivered directly to their mouth, no captive orca has lived its full life expectancy. For females, 85% of them don’t make it past 25. In the wild, a female matriarch can reach over 100 years old and mortality rate is very low in healthy populations.

Dorsal fin collapse

The tallest of all cetacean dorsals is the male killer whale. At 1.8 metres it is supported by fibrous connective tissue! Swimming fast, in a straight line and down to deep water keeps pressure on the fin, causing it to stay straight up. In the wild less than 1% of male orcas will experience dorsal fin collapse, where the fin folds over to one side. No wild females have ever been observed with this.

100% of captive males will have a collapse fin, as well as some females. Restricted mobility, and slow movements causes less pressure, as well as potential psychological changes, chemicals in water, dehydration, medication and the animals diet may all be factors.

Unnatural diet

Orcas will feast on almost anything from fish to birds, sharks, whales and even some land animals such as deer when they cross through marine environments. Each population around the world has a different diet preference and these groups will have specialised hunting methods that have been passed down through hundreds of years worth of generations. Some are mammal eating, others will only feed on specific fish and others will do both.

Orca can spend up to 90% of daylight hours foraging and travelling long distances. In captivity, they are hand fed frozen fish. This has a lower water content than fresh and can cause chronic dehydration. The solution is to feed ice and gelatin. This is extremely unnatural to a wild orca and inhibits their evolved behaviour of hunting.

Oral degradation

Orca have one set of conical teeth to last a lifetime. 40 to 56 interlocking, they are about 4 inches long and conical shaped. Designed to grip and tear prey into smaller pieces. Tooth wear is natural over decades and can be more severe with some prey items such as sharks! In captivity the orcas diet has zero impact on their teeth.

The damage and wear observed is caused by the confined conditions where they bite on concrete or metal bars due to boredom or aggression. This causes teeth to fracture or break and leaves the tooth exposed to decay and infection which can then be deadly.

Keepers will step in here and undertake dental work up to three times a day without any pain relief. Captive animals have also been observed to grind their teeth on the pool, this leaves no teeth left. No wild orca has ever been seen with this.

Forced mother and calf separation

Orcas are known to have very tight family bonds with the older females experiencing menopause to be able to live longer to care for their adult young. Males will spend their entire life with mum, while females only disperse to take care of their own young. Although they are never too far away with the grandmother stepping in regularly to teach culture, techniques and other aspects of life in the ocean.

Marine parks insist on separating mother and calf pairs at a very early age. Only four times in history was it necessary, due to aggression or severe medical interference. Once separated, orca have been observed injuring themselves, becoming “depressed” and showing repetitive and unnatural behaviour.

Separation is detrimental in particular to female calves who will then show aggression or often reject their own calves when they are artificially inseminated.

A wild mother orca carried her dead calf around for 17 days in a display of grief. Her family pod brought food to her and stayed by her side the entire time.

Excessive aggression

A manipulation of family groups and the creation of artificial pods who would normally never interact in the wild can create stressful and tense living situations in captivity. Tank mates may injure or even die due to aggressive encounters. This could be from ramming, tail slapping but mainly from “raking”.

Raking in the wild coincides with assertion, dominance and also rough play and it is caused by dragging teeth along the skin of another whale. However it can also be from assistance, such as by a ‘midwife’ during a tricky birth or when a family member is sick or injured other orca will keep it afloat using their teeth to grip, as they lack hands or arms to hold up.

Orca Dominance

Some orcas in captivity are completely covered in rake marks as other orca show extreme dominance. You don’t need to look for long to read about severe and confronting captivity tragedies. Some orca have lost huge chunks of skin and flesh exposing bone, others have been hit so hard they have blood coming from their mouth and blow hole. Some have lost teeth, and many have endured prolonged torture and aggression causing psychological trauma.

Unusual Behaviour

Kandu, a matriarch at SeaWorld San Diego bled to death in 1989 after an incident during a performance. For 45 minutes she sprayed blood from her blowhole after fracturing her upper jaw and severing arteries. Her 11 month old calf (who was still drinking mum’s milk) was present for the entire ordeal and swam circles around her lifeless body as it sank to the bottom of the pool.

Kandu hurt herself when she tried to ram a “foreign” orca and ended up hitting the tank wall. This was not the first time these two orca had altercations but were still kept together. In the wild these two females would have never been in the same ocean, let alone in the same confined space.

There are many more issues which include lack of mental stimuli, limited space, unusual behaviour and extended UV rays exposure. You can only imagine the compounding impact these issues would have on an orca behaviour in captivity.

Fate of captive whales

The fate of whales and orcas in captivity is not positive. They do not live full lives. They are deprived of crucial family bonds, their inherent cultures and the challenging marine environment they have evolved to not only thrive but dominate in.

How many orca are in captivity in 2021?

58 orca are still in captivity. 27 were wild caught and 31 were captive born. 173 orca have died in captivity since aquariums and zoos started housing them in the 1930’s. 2018 was the most recent capture with 10 caught in Russian waters to be sold to China. The amount of public pressure and a sale that fell through meant the whales were abandoned in small sea pens with no care. A huge effort was undertaken to release them back into the wild over a year after they were caught.

Education

North American zoos and aquariums have over 1 million visitors each year. The rise in Orca popularity came at a time when they first started appearing in tanks. However television programs and movies were also enhancing the whale’s popularity as it reached a wider audience. Captive animals can act as ambassadors to species which are endangered. It is too hard to say if orca would have the same human interest if they were never kept in captivity. But I believe we would still love them just as much.

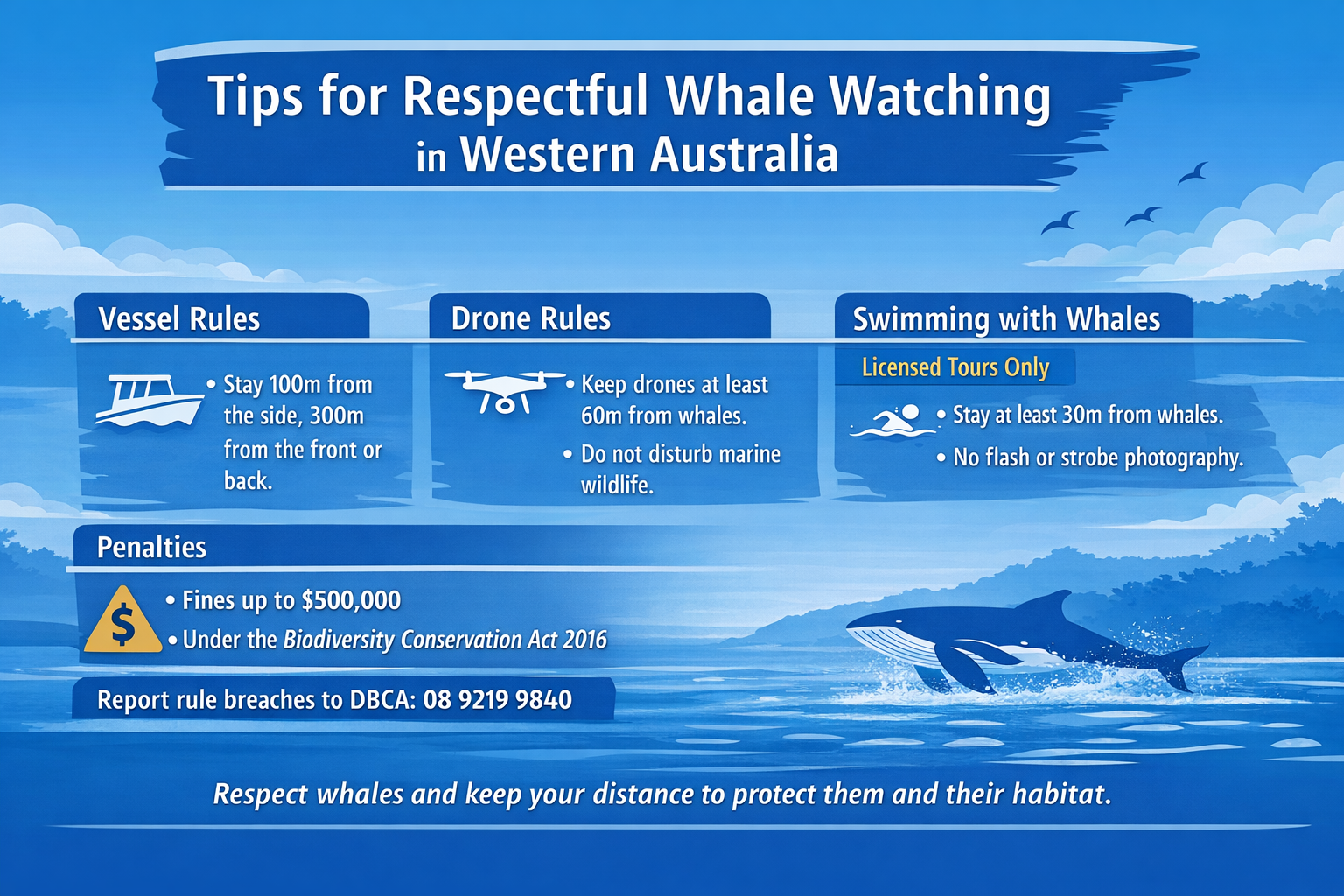

The rise in expeditions to wild orca populations has taken off in the last decade. Equipped with more knowledge and a greater value on animal ethics a wild orca tour is the better (and should be the only) option to see these apex predators. Not all tours are made equal though.

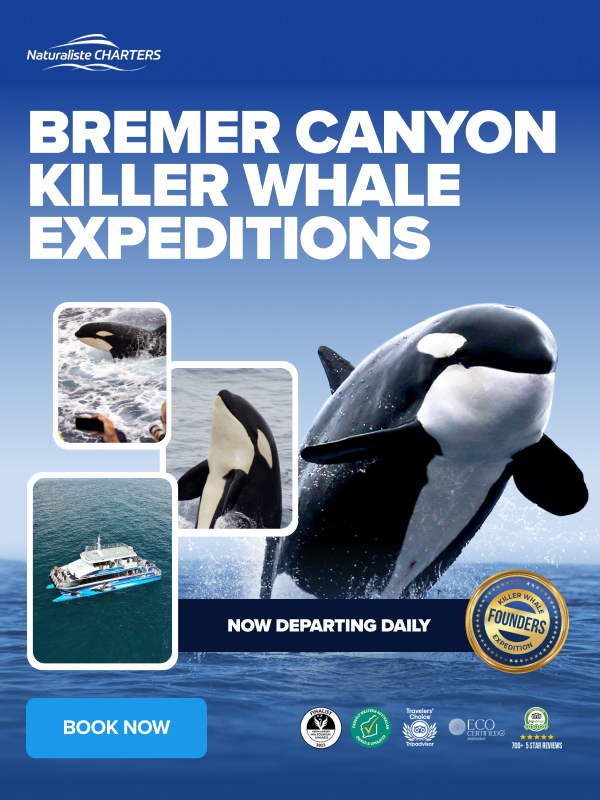

Choose to experience orcas in the wild

Killer Whale Expeditions in Bremer Bay are a world-class way to watch wild orca. Naturaliste Charters conduct tours daily from December through to April. Each expedition is led by an expert marine biologist and experienced team. Bremer Bay Killer Whales are a perfect look into the wild lives of killer whales, their culture and their strong family bonds.

Information obtained from the Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals; Wursig, Thewissen and Kovacs, 2018

Information obtained from Inherently Wild on the subject of Dorsal Fin Collapse